Speed of the future

Wake from your sleep

The drying of your tears

Today we escape, we escape

Radiohead – Exit Music (For A Film)

When we speak of speed, we generally refer to a phenomenon that characterizes the rapidity with which a quantity varies according to the variable on which it depends, or the rapidity with which the phenomenon unfolds over time.

Daniele, the protagonist of Yuri Ancarani’s film “Atlantide”, seeks through speed, redemption from a life lived on the margins, a life he seems to experience only through the subsultory movement caused by the keel of his boat on impact with the surface of the water in the Venice lagoon.

Rather than “simple” speed, what Daniele is looking for is rather, an escape velocity, which is defined in physics as the minimum initial speed that a body must possess to escape the attraction of a gravitational field, which in this case, we could equate with life itself. There is nothing in his life that seems to interest him more than the possibility of propelling his boat at a higher speed than those reached by other teenagers’ boats. Teenagers who populate the outskirts of Venice, living lives based on the search for quick and elusive pleasure, made up of industrial snacks, cocaine, and being part of a pack, whose internal rules are based on the affirmation of self over others.

Mechanisms that are constantly being pushed further and further by the need to reaffirm themselves ceaselessly and that force one to live life in constant escape, passing through decadence, loneliness, and emptiness without necessarily being able to leave them behind, thus elevating failure to an achievement.

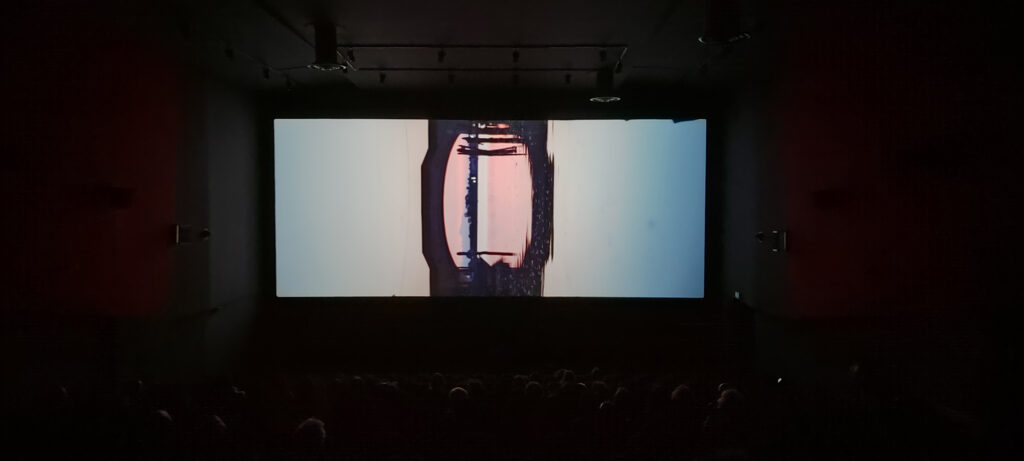

The trajectories drawn by the little boats launched at great speed by the teenagers during the film’s time span are silhouetted, by contrast, against the majestic, timeless fragility of Venice. The city is the absolute other protagonist of Ancarani’s film, it is both subject and narrative, it is the container that gives form to the water on which the teenagers’ stories are reflected. After all, as Winston Churchill said: «We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us»[1]. The relationship between the form of the city and the lives of the boys is inextricably linked, marking their destiny and showing itself at the end of their personal stories, like a living being from which we are swallowed up. The sculptural presence of its architecture becomes almost organic when the artist, with his usual precision in thinking up shots, turns the camera 90 degrees. We now find ourselves in the belly of the city, that part that cannot be perceived, or indeed understood, living only in the jolts of the waves of the lagoon’s surface. We descend through its intestine as if we were in a mythical place of shapes and colors, an almost psychedelic space; a continuous passage between below and above, inside and outside, cause and effect.

This place brings us back to the title of the film, Atlantis, an island that we have come to know in Plato’s dialogues as the place «that stood on the opposite side, around what is really the sea»[2] and which man has been searching for over the centuries, wanting to believe in its existence. Because man needs a myth, a utopia, to be able to keep going towards his future; Eduardo Galeano said that utopia is like the horizon, you walk two steps and she goes two steps away, you walk 10 steps and she goes 10 steps away. No matter how much you walk you will never reach it. But then what is utopia for? Precisely that, because we never stop walking.

Daniele and the other youngsters speeding against the backdrop of Venice/Atlantide are a generation that seems to have lost their utopia, disconnected from their future, they seem lost in the trajectories of their lives as the future comes at them with all its speed, leaving them no way to escape, no matter how fast they go.

Stefano Romano

[1] Sir Winston Churchill in his speech to the House of Lords, 28 October 1943.

[2] Plato, Dialogues, Timaeus, 17-27, c. 360 BC